Lesson 4: National Preparedness System

Lesson Overview

|

|

|

|

|

|

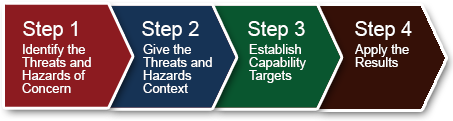

Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment

Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment

|

|

|

THIRA Process Outputs

THIRA Process Outputs

|

THIRA Benefits and Results

THIRA Benefits and Results

|

Learning More about THIRA

Learning More about THIRA

|

|

Examining Current Capability Levels

Examining Current Capability Levels

|

Involving the Whole Community

Involving the Whole Community

|

Example: Analyzing Risks and Estimating Capabilities

Example: Analyzing Risks and Estimating Capabilities

|

|

Leveraging the Whole Community

Leveraging the Whole Community

|

Whole Community Case Study: Miami-Dade C.O.R.E.

Whole Community Case Study: Miami-Dade C.O.R.E.

|

Mutual Aid and Assistance

Mutual Aid and Assistance

|

What Are Mutual Aid and Assistance Agreements?

What Are Mutual Aid and Assistance Agreements?

|

What Are Mutual Aid and Assistance Agreements? (continued)

What Are Mutual Aid and Assistance Agreements? (continued)

|

What is Included in Agreements?

What is Included in Agreements?

|

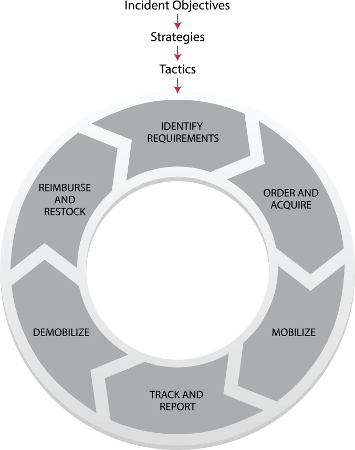

Resource Management

Resource Management

|

|

Resource Credentialing and Typing

Resource Credentialing and Typing

|

Training and Education

Training and Education

|

Case Study: Training for the Whole Community

Case Study: Training for the Whole Community

|

Additional Community Training Resources

Additional Community Training Resources

|

|

An Integrated Approach

An Integrated Approach

|

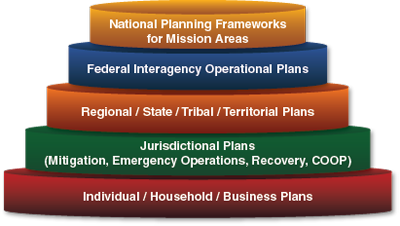

National Planning System

National Planning System

|

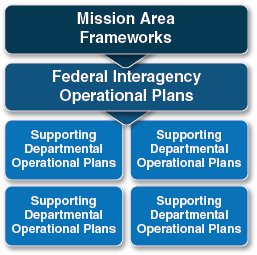

National-Level Planning Documents

National-Level Planning Documents

|

National-Level Planning Documents (continued)

National-Level Planning Documents (continued)

|

Planning Guidance for the Whole Community

Planning Guidance for the Whole Community

|

Case Study: Whole Community Planning

Case Study: Whole Community Planning

|

|

Exercises

Exercises

|

Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP)

Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP)

|

Training and Real-World Events

Training and Real-World Events

|

Lessons Learned and Corrective Actions

Lessons Learned and Corrective Actions

|

|

|

Reviewing and Updating (continued)

Reviewing and Updating (continued)

|

|

|

|