Welcome to IS-0238: Video Transcript

Hello. I am Gene Shearer, the Supply Chain Advisor for the FEMA Logistics Management Directorate. I coordinate efforts to better understand the private sector supply chains and present this knowledge and understanding to help inform FEMA planning and relief decisions. As emergency managers, it’s our mission to help people before, during, and after disasters. To this end, it’s important to understand our limitations.

Did you know that, if FEMA combined all of the food and water that it has stored in the continental United States, we’d only be able to feed one of our most populous cities for a few days? That’s why it’s so vitally important to understand the operations and vulnerabilities of private sector supply chains that provide the products and commodities our population needs each and every day.

As emergency managers, we simply cannot replace the volume and velocity of the private sector. That is why we must work to restore the pre-disaster flows of goods and services as soon as possible. At a minimum, we should ensure that our relief efforts do no harm to this restoration process. This course will provide you the basic understanding of the critical concepts of supply chain flow and resilience. This course is based on National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2020 report, “Strengthening Post-Hurricane Supply Chain Resilience: Observations from Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria.” You will hear from many of the experts who contributed to this ground-breaking report during this course.

Good luck with your learning experience.

Course Overview

The goal of this course, IS-0238: Critical Concepts of Supply Chain Flow and Resilience, is to strengthen State, Local, Tribal and Territorial Emergency Managers’ understanding of local supply chain dynamics; improve information-sharing and coordination among public and private stakeholders; and provide State, Local, Tribal and Territorial Emergency Managers with the knowledge of potential and experienced post-disaster supply chain disruptions, management efforts, and best practices.

Objectives: At the end of this course, you will be able to:

- Explain basic supply chain concepts and associated challenges

- Describe the basic components of a supply chain, common disruptions to supply chain flow, and ways to respond to them

- Describe concepts of bottlenecks and their impacts on supply chain management

- Describe the potential impacts of a disaster on supply chains

- Describe concepts of supply chain resilience before, during, and after a disruption

This course should take approximately 2 hours to complete.

Screen Features

-

Select the Close button to exit this window and access the menu listing all lessons of this course. You can select any of the lessons from this menu by simply selecting the lesson title.

-

Select the Glossary button to look up key definitions and acronyms.

-

Select the Help button to review guidance and troubleshooting advice regarding navigating through the course.

-

Track your progress by looking at the Progress bar at the bottom of each screen.

-

Follow the instructions that appear on each screen in order to proceed to the next screen or complete a Knowledge Review or Activity.

- Select the Back or the Next buttons at the bottom of screens to move backward or forward in the lesson. You may also use the "Navigation" panel located on the left side of the screen to navigate between pages and lessons. Note: If the Next button is dimmed, you must complete an activity before you can proceed in the lesson or use the left hand "Navigation" to bypass it.

Navigating Using Your Keyboard

Below are instructions for navigating through the course using your keyboard.

Use the "Tab" key to move forward through each screen's navigation buttons and hyperlinks, or "Shift" + "Tab" to move backwards. A box surrounds the button that is currently selected.

Use the "Tab" key to move forward through each screen's navigation buttons and hyperlinks, or "Shift" + "Tab" to move backwards. A box surrounds the button that is currently selected.- Press "Enter" to select a navigation button or hyperlink.

Use the arrow keys to select answers for multiple-choice review questions or self-assessment checklists. Then tab to the "Submit" button and press "Enter" to complete a Knowledge Review or Self-Assessment.

Use the arrow keys to select answers for multiple-choice review questions or self-assessment checklists. Then tab to the "Submit" button and press "Enter" to complete a Knowledge Review or Self-Assessment.- Warning: Repeatedly pressing "Tab" beyond the number of selections on the screen may cause the keyboard to lock up. Use "Ctrl" + "Tab" to deselect an element or reset to the beginning of a screen's navigation links (most often needed for screens with animations or media).

- JAWS assistive technology users can press the "Ctrl" key to quiet the screen reader while the course audio plays.

Receiving Credit

To receive credit for this course, you must:

-

Complete all of the lessons. Each lesson will contain various different types of content including text, videos, audio, transcripts, and knowledge reviews. Study all content provided.

It is important to allow enough time to complete the course in its entirety.

It is important to allow enough time to complete the course in its entirety.

Each lesson shows an approximate time to complete on the lesson's overview screen.

Remember . . . YOU MUST COMPLETE THE ENTIRE COURSE TO RECEIVE CREDIT. If you must leave the course during your training, make note of the current location and use the Navigation found on the left hand side of the screen when you are ready to continue. - Pass the final exam. The last screen provides instructions on how to complete the final exam.

Looking Through a New Set of Eyes: Video Transcript

Welcome to IS-0238: Critical Concepts in Supply Chain Flow and Resilience. Hi there. My name is Paul Lopez . I am an Emergency Manager, and I'll be leading you through this course.

Traditionally, Emergency Managers who work with supply chains, like you and I, have been logisticians whose tasks were to fill the gaps by creating relief channels. But recent history has shown that communities are more resilient when our focus shifts on restoring the flow of goods through existing channels. But to be able to do that, we need to understand how private sector supply chains operate and what they need to function effectively. In this course, you are also going to learn that Emergency Managers can play a different role in meeting the needs of a community after a disaster event.

The old motto was "Go Big, Go Early, Go Fast." The new motto is "Look, listen, collaborate, and facilitate."

I challenge all of you who are taking this course to look at relief with a new set of eyes. Now, let's get started.

Lesson 1 Objectives

At the end of this lesson, you will be able to:

- Describe the function and components of a supply chain

- Describe the fundamental challenge of supply chain management

- Describe the two features that complicate supply chain management

This lesson should take approximately 30 minutes to complete.

Supply and Demand

To get the goods and services we want and need, we rely on an economic system of supply and demand. In it, potential buyers signal their demand and their willingness to offer something in value in exchange to suppliers. Suppliers then organize to produce and deliver the desired goods and services to consumer markets.

These supply and demand forces move goods across considerable distances, and over time, they have created significant flows of information, money, and supplies. To increase the volume and velocity of trade, better transportation routes, ports, shipping hubs, and marketplaces were developed. The result is a complex global network of suppliers, manufacturers, transporters, distributors, retailers, and consumers that we commonly refer to as supply chains.

Understanding how supply chains operate, how they can be disrupted, and how they recover from disruptions is fundamental to increasing supply chain resilience and meeting Community Lifeline needs in an evolving all-hazards environment.

What is a supply chain? Video Transcript

What is a supply chain? A supply chain is a self-sustaining network of companies used to deliver products and services from raw materials to end customers.

Here's a basic supply chain for the table-making industry. Wood supplier, component suppliers, table manufacturer, transportation partners, retailers, and customers. The raw materials move from the supplier to the manufacturer. Then, the tables move to the retailers, and finally to the people in the community. The goal is to move the products as quickly and cost-effectively as possible.

There are three basic flows that connect the supply chain entities together: commodities, information, and finances. The commodities, which can be physical materials and products, flow downstream from the supplier to the consumer. In some cases, products can move in reverse, in the case of returns or rejections. Money, in the form of cash or credit moves upstream, from customers to retailers, manufacturers, and to their suppliers. Information that guides production, transportation, and distribution decisions flows downstream. On the other hand, information that guides demand flows upstream.

What is needed to operate/enable a supply chain?

- All the entities in a supply chain have primary inputs they require to operate. These inputs include:

- Water

- Power (electricity, fuel)

- Information (telecommunications, payment processing, etc.)

- People

- If other required materials, like certain ingredients, components, or processing materials, are not available, an entity may still be able to operate for a few days. But the entity's output may be reduced or modified as a result of the shortage.

How does a supply chain operate under normal conditions? Video Transcript

Consider a supply chain of food products. First-line handlers sell and transport the prepared agriculture products to both processors and wholesalers. Processors include the meat packers, bakeries, and other companies that turn raw agriculture products into packaged food products. Processors then sell the finished food products to wholesalers. Wholesalers store the food products purchased from the first-line handlers and processors, and then sell and distribute these products to retailers.

The number of steps any individual food product goes through can vary widely. Fresh produce can be sold directly from first-line handlers to wholesalers, or even retailers. Packaged baked goods may incorporate ingredients from multiple first-line handlers, processors, and even wholesalers, before they are processed and packaged and sold. Imported food products can enter the supply chain at almost any stage.

The final step in the supply chain is getting finished, packaged food products to customers.

Retailers include grocery stores and other retail outlets, or big-box stores, where consumers buy food products to prepare and eat at home, as well as the food service industry. The retailers price, display, store, and sell the food to consumers. In many cases, the retailers also perform some additional processing, for example, in-store meat departments and bakeries. The supermarkets, and even smaller stores like convenience stores and tiendas, are the neighborhood-level link for populations to obtain food.

The other major component of the food supply chain is the transportation network. Unlike water and petroleum products, most agricultural goods cannot be moved by pipeline. Instead, the food supply chain relies on transport by train and ship for long distance movement of raw and bulk agricultural commodities. After food is packaged at processors, however, the majority of transport occurs by truck.

Global Supply Chains

- Some supply chains have one or more entities located outside of the U.S. These can include raw material and component suppliers or manufacturing plants.

- Offshore sourcing or manufacturing is a strategic choice some companies make to reduce costs. However, the time and cost to transport raw materials and finished components over long distances becomes an important factor in supply chain management.

Source: C.H. Robinson

Global Supply Chains: Audio Transcript

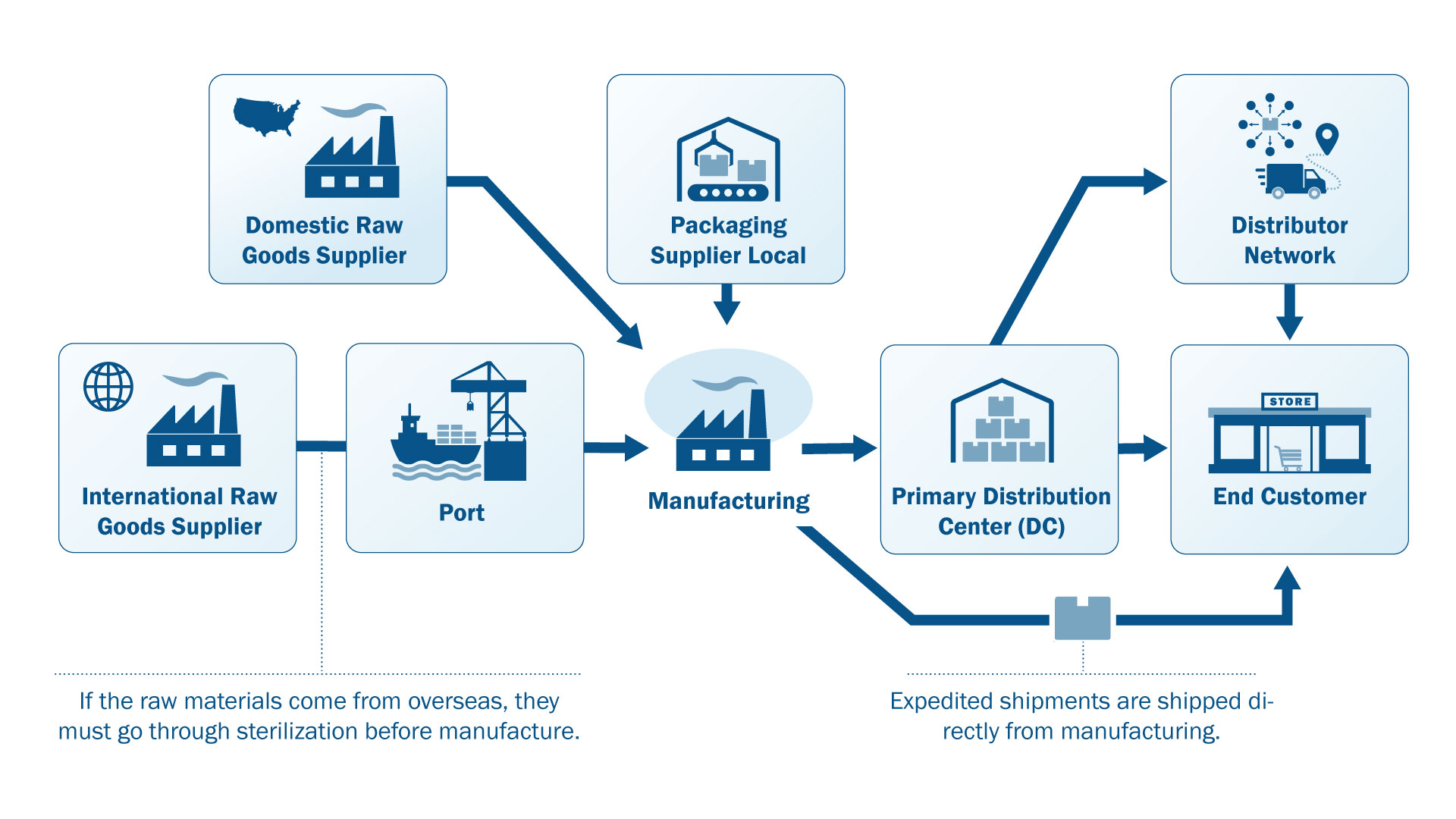

In this diagram, a manufacturing plant has both a domestic and an international raw goods supplier. Raw goods from overseas are transported, generally by ship, to the U.S. Raw goods must go through a sterilization process before they can be used in the manufacturing process. The manufacturing plant also has a local packaging supplier. Finished goods can be shipped directly from the manufacturer to the retail outlets where they are sold to the end customer or to a primary distribution center. From there, the goods are either shipped directly to the customer or routed through a distributor network and then onto the retail outlets where they are bought by end customers.

Supply Chain Complexity: Video Transcript

Supply chains can be very complex. Let's look at two table examples.

The first is an all-wood table that will be sold in retail outlets. It is made of solid oak, stainless steel screws, and has a rubbed oil finish. Each of those materials (oak, linseed oil, screws) is made from different raw materials and is produced by a different supplier. The wooden parts of the table are created and then assembled with screws in a factory. Then the oil finish is applied. The completed table is shipped to a warehouse, and then to a store.

Once purchased, the table is delivered to the customer's home.

The second example is for a table that will be shipped unassembled directly to the customer. This table has a solid oak top with a rubbed oil finish, stainless steel legs, and screws. It will also require a cardboard box, paper instructions, and a plastic bag for the screws. This ready-to-assemble table manufacturer is able to access the same suppliers as the retail-oriented manufacturer, but also needs to source stainless steel legs, printed instructions, and plastic bags. The raw materials for the plastic bag are petroleum based. Stainless steel legs and paper instructions come from different suppliers. The tabletop is created and given its oil finish in a factory. The finished tabletop and other components are shipped to a packaging facility where the screws are put into a plastic bag and boxed up along with the tabletop, legs, and assembly instructions. The box is transported to a distribution center.

Once an order is received, the box is delivered directly to the customer's home where it is assembled on site.

Supply Chains in Your Jurisdiction

Look at your jurisdiction:

- Where are raw materials or food products sourced in your area?

- Where are the manufacturing/processing facilities?

- Where are the warehouses?

- Where are the distribution centers?

- Where are the retailers?

- Where are the refineries, pipelines, generating plants, and electrical transfer stations?

- Where are the truck stops and gas stations?

- Where are the railroads, inland ports, and coastal/riverine ports?

Supply Chains are Ecosystems

- While supply chains are made up of many companies, together they form an interdependent community or ecosystem.

- Each member relies on the others to maintain the balance and stability of the system. Government policies, availability of finance, workers’ strikes, and other decisions impact companies upstream and downstream in the supply chain.

Supply Chains are Ecosystems: Audio Transcript

Hello, I am Brian Koon, the Vice President of Homeland Security and Emergency Management for IEM, a company that helps government prepare for and respond to natural and man-made disasters, including planning for and overcoming supply chain disruptions.

After Hurricane Maria, FEMA contractors began paying premium prices to truckers on the island of Puerto Rico to expedite the movement of supplies through the relief supply chain.

This had the effect of siphoning off the already limited supply of truckers from grocery stores, wholesalers, construction, and beverage distributors. Retailers couldn't keep their store shelves fully stocked. When consumers saw empty shelves, it reinforced their sense of uncertainty and increased demand. Seeing empty shelves that should have held water was especially disconcerting.

The decision to increase truckers' wages also had an impact on the public sector supply chain because Highway and Transportation Authority contractors also left their jobs for the higher pay. This greatly reduced the number of trucks available for road work and slowed the pace of road repairs across the island.

Decisions made at one point in a supply chain have a rippling effect up and down the network.

This case study appeared in the Center for Naval Analysis report, Supply Chain Resilience and the 2017 Hurricane Season: A collection of case studies about Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria and their impact on supply chain resilience (2018).

Supply Chain Management Challenge: Matching Supply and Demand

- It has always been a challenge to decide what, when, how, and where to move supplies in order to match supply with demand. It is an even greater challenge to do it in a responsive, accurate, and cost-effective manner.

- Supply chain managers work to streamline their businesses' supply-side activities to provide the greatest customer value and gain a competitive advantage in the marketplace.

What if demand changes?

Demand volume (and supply) fluctuates over time. Some demand variability can be predictable. At other times, demand surges and drops are unpredictable. Select the buttons below to learn more about demand variability.

Predictable

Some demand variability can be predictable. For example, there are seasonal demand shifts, like the increased demand for water and other cold beverages in the summer. Scheduled equipment maintenance downtime also will have a predictable impact on production output.

Unpredictable

Other demand shifts are unpredictable. Customers may decide to reduce or change their purchasing patterns. A sudden equipment failure can reduce supply. Similar types of variability can also occur in the transportation phase of a supply chain.

Managing with Demand Forecasts: Video Transcript

Managing with Demand Forecasts.

If demand variability were entirely predictable, with no deviation between planned and actual production, it would be possible to make supply chain decisions that could precisely adjust supply to meet demand. This is possible for some season-related trends. For example, beverage companies know that higher temperatures in the summer create a surge in demand for water and soft drinks. They rely on overproduction during colder seasons to stockpile inventory to meet the predictable summer demand.

However, because there is some unpredictable variability in demand for all supply chains, many supply chain decisions must be made on the basis of demand forecasts.

Companies can choose from several methods to create demand forecasts, but all begin with analysis of market data and historical data. This includes past sales and demographic and economic data. Corporations use large-scale integrated information systems to capture and analyze sales and economic data on the factors that drive demand for their products or services. That information is fed into computer models to generate baseline statistical forecasts. To confirm those forecasts, companies gather and analyze business intelligence from market experts, end users, and other stakeholders. After making adjustments based on business intelligence, the next step is to achieve a consensus on the forecast. The next step is to generate a demand plan that will include contracting with vendors to supply the predicted amounts of materials and components they will need to meet the anticipated demand. This is a cyclical process that some companies repeat several times during the year. It is important to remember that the more complex and/or geographically dispersed a supply chain is, the more difficult it is to make accurate forecasts.

Demand Forecasting Challenges

Even under the best or normal conditions, forecasts are never perfect. When there is a sudden, unpredicted shift in demand, sometimes it takes companies a while to catch up.

Demand Forecasting Challenges: Audio Transcript

Hi, I’m Phil Palin. I’ve worked with the National Academy of Sciences, the Department of Homeland Security, FEMA, and many others to advance supply chain resilience in catastrophic contexts.

Campbells Soup relies on production delivery methods to match its near-term supply with real-time consumer demand. For many years, more varieties of soup have supported higher volume sales. In recent years Campbells has sold over 400 million cans of soup per year. But in Spring 2020, Campbells experienced sudden pandemic-related increases in demand for all of its soup and especially for a few classic flavors like Chicken Noodle. Depending on place and product, demand increased one-third, one-half, or even double in just one week or two. No well-managed production process has that kind of excess capacity. So, the company discontinued lower demand varieties while streamlining its processes to produce much more of a smaller set of high-demand varieties. Within several weeks, the company was satisfying customer demand for the highest-demand products.

At the same time, the Personal Protective Equipment industry, which produces medical gowns, nitrile gloves, N95 masks, also experienced a massive jump in demand. Like canned soup, PPE is a low-margin product that requires careful cost containment to maintain sustainable flows. But, where Campbells was able to reorganize its huge capacity to meet, lets say, a doubling of demand, the PPE industry had a smaller pre-existing capacity, usually much farther away from U.S. consumers. And it needed to use this to respond to a multiplication of demand that, some has estimated, exceeded 100 times pre-existing flows.

For high-volume, high-velocity supply chains, like those used for canned soup or PPE, production capacity is the outcome of multi-year, high-cost capital investments. The system is resilient within the boundaries of reasonable commercial expectations, but not within the boundaries of catastrophic risk.

Cycle Time Challenges

Source: HERO

- Cycle Time is the total time it takes from the start to finish of a production process. There are separate cycles for every part of a company's operation, including order placement, sourcing of materials, manufacturing, and delivery.

- Cycle time is also referred to as “flow time,” “manufacturing lead time,” or “production lead time.”

- Changes inside and outside of the company can impact the time required to complete a cycle. Lack of raw materials, transportation or equipment breakdowns, labor shortages, disruptions due to natural disasters, and human errors are all factors that can impact one or more cycle times.

Real vs. Perceived Shortages

- Demand and actual need are not the same. Shortages, and even perceived shortages, can increase the demand for a product. Long cycle times can exacerbate shortages.

- Humans have interesting psychological responses to scarcity environments. They place a higher value on an object that is scarce. If they want it and can't find it, they only want it more.

- Another human reaction to scarcity is anticipated regret, or “fear of missing out” (or FOMO). Shoppers buy something they don't need now to avoid running out in the future. Hoarding and panic buying are the results of perceived scarcity and FOMO. Suppressing the fear of missing out is an important aspect of demand management.

Real vs. Perceived Shortages: Audio Transcript

Hello, I'm Dan Green. I serve as a Logistics Section Chief from FEMA Region 3. Understanding how systems that support critical lifelines operate under adverse conditions help emergency managers prepare to deal with the consequences of an incident.

When a cyberattack shut down the Colonial pipeline for six days in May of 2021, the impact was felt up and down the East Coast—even in places that didn't receive fuel from the pipeline. Gas stations in Tampa and Miami, cities that receive their fuel by barge, ran out of fuel because of panic buying. The perceived shortage purchasing continued even after it was announced that the pipeline would resume operations. In areas that were affected by the outage, demand for fuel was higher than normal as drivers filled their tanks, containers, and even plastic bags, in an attempt to avoid running out of gas.

Impact of Rationing

True increases in need and demand sometimes result in need for rationing. When resource decisions are made, they can create more shortages, which result in a cascading impact.

Impact of Rationing: Audio Transcript

Hello, I'm Dan Green, a Logistics Section Chief from FEMA Region 3, and I served as the fuel management officer for FEMA in Puerto Rico following the landfall of Hurricane Maria.

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Maria, demand for gasoline on Puerto Rico jumped more than 40 percent. The increase was due in large part for the need to fuel diesel generators. However, on September 25, 2017, nine days after Maria, only 100 of the 1100 gas stations on the island had reopened.

To try to extend available retail supplies and treat customers fairly, many gas station operators began rationing purchases to $10 or $15 per customer. This helped to defuse social tension in the long lines, but it also made the lines longer, as many consumers would empty their jerry cans and quickly return to the line. Rationing just increased and accelerated the expression of consumer demand.

On September 25th, the Puerto Rico Secretary of Consumer Affairs made retail rationing illegal. Removing the arbitrary limits on consumer purchases reduced overall consumer cycling.

At the same time, the curfew was extended by two hours. This gave the system more time to meet demand. And by the end of the first week, almost 700 gas stations had reopened. The day before, the governor had exempted fuel distributors from the curfew, allowing nighttime deliveries. By the beginning of the second week after landfall, the lines at the gas stations were much less dramatic. By October 3, the Puerto Rican fuel distribution system had reclaimed its preexisting capacity and was distributing roughly 30 percent more than it had before the storm.

This case study appeared in the Center for Naval Analysis report, Supply Chain Resilience and the 2017 Hurricane Season: A collection of case studies about Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria and their impact on supply chain resilience (2018).

Think About Shortages

- How did demand variability affect the PPE suppliers?

- How did cycle time impact their ability to meet demand?

- How did real and perceived shortages affect the supply of fuel in Puerto Rico and southern Florida?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of rationing scarce goods?

Lesson 1 Summary

By now, you should be able to:

- Describe the function and components of a supply chain

- Describe the fundamental challenge of supply chain management

- Describe the two features that complicate supply chain management